|

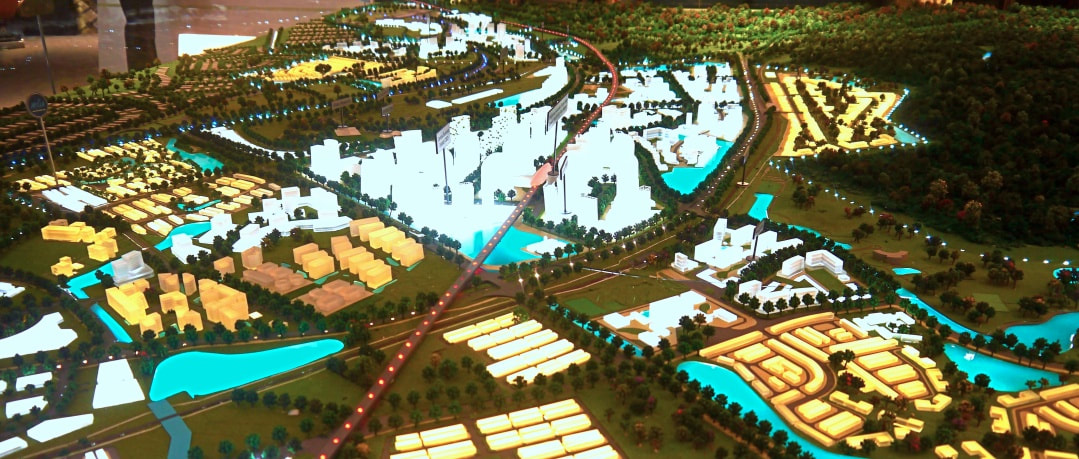

The iconic project would have benefitted both countries since Malaysia and Singapore are historically intertwined By Khalil Adis Since Malaysian Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin rose to power in 2020, the local political landscape has shifted rapidly. On the one hand, it has deeply polarised Malaysians in what they perceive as a ‘back-door government’. On the other hand, it has caused seasoned investors and political watchers do a double-take to decipher what is really going on. Against a backdrop of a pandemic, reports of political infighting, defections and ongoing corruption court cases from the previous administration, Malaysia’s political landscape appears to be a fractured one. From across the pond though, it looks like Malaysia has it all - a warm, tropical climate, rich in natural resources, a melting pot of different races and cultures and one of the very few countries where you can own freehold property. However, a quick glance on social media shows that Malaysians are tired about the constant politicking which they feel have hindered the country’s progress. Foreign direct investment affected by pandemic So how has Malaysia fared so far? Figures from the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA) showed that in 2020, net foreign direct investment (FDI) fell 56 per cent to US$3.4 billion in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, Malaysia’s net FDI inflows stood at RM13.9 billion representing a decline from RM31.7 billion in 2019. "Malaysia’s lower net FDI inflows in 2020 is not necessarily an unfavourable sign, when taking into consideration the global investment landscape and the uncertainties that prevailed during the year," said MIDA in its report. While Malaysia’s FDI last year was affected by the pandemic, the lack of political will to see through certain projects may affect investors’ confidence. KL-Singapore HSR project One such example is the cancellation of the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore High Speed Rail (KL-Singapore HSR) project. Malaysia and Singapore have since the dawn of time been historically intertwined. Since many Singaporeans have relatives living in Malaysia and vice versa, the KL-Singapore HSR project would have provided immense benefits as it will allow the flow of goods and investments especially in the hard to reach cities like Seremban, Ayer Keroh, Muar and Batu Pahat. It would also have provided a much-needed boost for the already muted property market in Iskandar Malaysia by tapping onto Singapore’s position as an international aviation hub and among those living in Kuala Lumpur. Over in Seremban, the upcoming Malaysia Vision Valley would have benefitted from the train service since transportation connection over there is patchy at the moment. Spanning from Nilai to Port Dickson and with a proposed area of 108,000 hectares, the Malaysia Vision Valley will see the development of high tech, logistics, education, health, tourism and sports industry. Should the KL-Singapore HSR project proceed, the Malaysia Vision Valley would be able to tap onto local talents from Kuala Lumpur and from the international market in Singapore. Likewise, it would have resulted in the flow of investments and skilled workforce to Bandar Malaysia, Singapore and vice versa. Sadly, this was not to be. History repeating itself? Looking back, one cannot help but feel that the KL-Singapore HSR project’s fate echoes eerily similar to the previous scenario in the 1980s and 1990s which had deterred Singaporeans from investing in Johor. Similarly, Iskandar Malaysia started out full of promises in 2008 until interest somehow fizzled out sometime in 2016. Once an investors’ darling, Iskandar Malaysia is now facing a severe housing supply glut which has been further exacerbated by the Movement Control Order (MCO) and travel restrictions. Meanwhile, Medini, a dedicated special economic zone continues to be a ghost town when night falls. One source who was involved in the joint-venture project between Singapore and Malaysia had complained about the lack of progress and the lack of political will to make things happen. Adding to the complication is the powers of the state versus the federal government since land in a state matter. Such bureaucratic red tapes is bound to create frustration. The source has since left. It is worth noting that in July 2019, Pinewood Group pulled out of Iskandar Malaysia Studios (IMS) officially ending their 10-year partnership by mutual agreement with the local partners. A glimmer of hope The only saving grace right now is the Johor Bahru – Singapore Rapid Transit System (RTS) Link. Slated to commence passenger service by end-2026, the project will link Woodlands North MRT station to Bukit Chagar. Still, the expected economic spillover impact from the RTS Link is minute when compared to the KL-Singapore HSR project. Last month, the World Bank Group said Malaysia will need to relook at some of its policies and to rebuild them towards attracting more quality investments into the country that at the same time would provide more jobs for the people. “There should also be a more coordinated promotion effort to get a higher return of investment and finally, it is important to have continuity in policy and direction as well as structural reforms,” Richard Record, the World Bank Group’s lead economist was reported as saying. This was in response to a question on how Malaysia could attract more FDI to catch up with countries in the region. Perhaps, one day, when travel restrictions are lifted, Malaysia will revisit the feasibility of implementing the KL-Singapore HSR project once again.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Khalil AdisAn independent analysis from yours truly Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|

100 Peck Seah Street

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed